Artistieke opleiding: Universiteit van Sarajevo, Faculteit architectuur (1973 tot 1977)

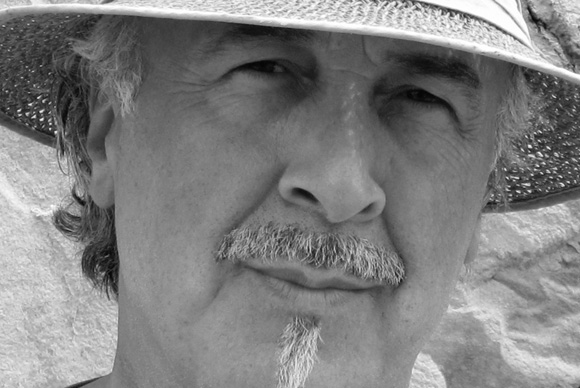

Mirso Bajramovic is visual artist living and working in Gennep, the Netherlands.

He was born in Sarajevo, former Yugoslavia (present Bosnia and Herzegovina). Mirso received his artistic education at the University of Sarajevo, where he attended architecture-classes from 1973 until 1977. His career as an artist started in Dubrovnik, where he live from 1982 until his departure to The Netherlands, in 1986. Mirso is a member of Dutch GBK Artist association since the beginning of 1993. Mirso’s work was shown at over thirty solo exhibitions in The Netherlands, Germany, France and Belgium. His paintings can be seen in numerous private collections in the USA, Canada, Japan and Australia.

1988. Kunsthandel Brabant, Uden, The Netherlands

1989. Galerie La Porte, Gennep, The Netherlands

1991. De Wieken, Molenhoek, The Netherlands

1992. Kasteel Heijen, Heijen, The Netherlands

1992. St.Vinzenz Krankenhaus, Altena, Germany

1993. Kunstgalerie Toro, Wenray, The Netherlands

1996. Stadsschouwburg, Antwerpen, Belgium

1996. Kunstuitleen, Cuijk, The Netherlands

1996. Artifex, Cuijk, The Netherlands

1996. Salon international d’art contemporain, Nice, France

1997. Streekmuseum, Gennep, The Netherlands

1997. De Gele Rijder, Arnhem, The Netherlands

1997. CBKN, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

1998. Mariendael, Sint-Oedenrode, The Netherlands

1998. Het Petershuis Museum, Gennep, The Netherlands

2000. Dr. Anton Philips zaal, Den Haag, The Netherlands

2001. Kunst-Ahoy, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

2001. Beursgebouw, Eindhoven, The Netherlands

2003. Villa Belriguardo, Kleve, Germany

2005. Cultureel Centrum Corrosia, Almere, The Netherlands

2005. Museum Het Petershuis, Gennep, The Netherlands

2006. Niersdal project, Gennep, The Netherlands

2006. Gallery De Bakkerij, Bergen, The Netherlands

2006. De Hamert, Wellerlooi, The Netherlands

2007. Kopstukken Project A77, Boxmeer, The Netherlands

2007. Kunst in het Maaspark, Mook, The Netherlands

2008. Bericht van licht, Museum Het Petershuis, Gennep, The Netherlands

2008. Kloster Graefenthal, Kessel, Germany

2009. Bugemeesters project, Stadhuis Gennep, The Netherlands

2010. “K@R-t-Blanche”, Roepaen, Ottersum, The Netherlands

2011. De Ontmoeting, Gennep, The Netherlands

2013. K(r)oningsportretten, Grote Kerk, Breda, The Netherlands

2013. ‘Ons Koningshuis’, Galerie Markant, Beilen, The Netherlands

2013. K(r)oningsportretten, Galerie Noord-Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

What is certain is that Mirso Bajramovic is an artist, a painter, and, furthermore: a Dutch painter. Question: can that epithet `Dutch` be inferred from his paintings as well as from his passport?

Is his art as sonorously Dutch as his voice and letters? Or did the Bosnian who integrated in `no time` in so exemplary a manner, remain an alien in the Dutch art world, one who becomes a foreigner (with mitigating circumstances), as soon as he sits down behind his easle? Were Spinoza and Descartes (to mention two of the most highly gifted and talked-about foreigners we ever had over here), despite all, still foreigners whenever they seriously started thinking or writing or something as thought-provoking?

Or have we, conversely, been taking them as our examples in finding out how to become just as exemplary Dutchmen as all those other well-brought up (Spinozist- or Cartesian-trained) `boys of Jan de Witt`? Quite a few foreigners became honorary Dutchmen, and so did us credit as well. And quite a few Dutchmen – including many painters – apprenticed themselves offshore in order to become universally respected Dutchmen in the end. To become is better than to be.

Allow me to state that we, the Dutch, should renounce our rights to almost all our exemplary Dutch painters, scientists and even clergymen as soon as we start having second thoughts about their Flemish, German, Italian French, Portuguese or even Hungarian (i.e. the Maris brothers) backgrounds. The Belgians, it has been claimed, apodictically, do not exist. Question: do the Dutch exist? And if they do, how many of them were once extremely rich or poor Flemish, French, Spanish, German, Italian or Portuguese immigrants or Indo-Dutchmen?

Another question: how many French artists are left if one disregards all foreign `French` artists – Dutchmen, Russians, Belgians, Algerians, Romanians, Japanese, Bulgarians, not to mention Bosnians, Serves and Croatians? Are there any American artists, apart from the Sioux, Comanches, Hopis, Zunis and Navahos, who are not the descendants of foreigners with or without residence permits – of Americans with unamerican countries of origin?

Now let me try to describe what happened to me, a Brabantian Dutchmen, when, speechless in countless ancient and modern languages, I was confronted with the first painting to which the Bosnian Dutchman Mirzo Bajramovic introduced me. A work from his hands. Which was `communicating itself` to me, very eloquently, and in immaculate Dutch, let me add. But alas, I did not come up with a reply. Not one word of Bosnian or Dutch occurred to me. Or rather: much too much occurred to me simultaneously, except for anything verbal, a single word in one of my innate or acquired mother or father tongues. But – let me repeat it – the painting with its extraordinarily refined enunciation was not to blame. No, I was offside and tongue-tied. Countless associations appeared on the tv-screen of my consciousness, but none was subtitled decently enough in any language or dialect to come out of my mouth decently-framed. The articulate painting had silenced me, so who can picture my distraction and understand that my silence had to do with overawe? And with a desperate attempt to express approval and admiration. Who can picture my bewilderment and explain to the artist that it was the inimitable quality of his painting which was reflected by my silence (which he did not imitate)?

In my position I should at least be able to speak up when a work of art or an artist reduces me to quiet admiration. And why. Now may I try to picture all those things which did not – but almost did – (instantly) occur to me on the right moment?

Well. I retrace the steps of my esprit de l’escalier, as I mount the stairs connecting the basement and top floor of my silence. What did initially occur to me was too trivial to be true, not worth expressing. But those same dreadfulnesses did become – after some days – the first words in a chain of associations which did merit reconstruction. `Oriental`, I had said, and `exotic`, expressions I most seldomly and reluctantly use. I’m afraid I even dished up some shameful generalities connected with the `Thousand and One Nights`. In any case: I thought the painting `SPLENDID` and, moreover, `GRAND` – and said so. Justifiedly so. Infinitely meaningful yet meaningless words. It was a large painting studded with undutch carbuncle-sized stars, which are as much beyond us, Occidentals, as that `Starry Night` painted by Van Gogh under a mediterranean sky. But I did not think of Vincent but of one of those medieval manuscripts, scalloped with planets and stars, which open up seventh heaven to us. Once I had got that far – close enough to the Van Eyck brothers, the Duc de Berry and that first Turkish luxury edition of the Koran in the British Museum – I finally started to feel comfortable in the language of Bajramovic and his `magnum opus`, entitled, no doubt, like so much modern art: `u.t.`, `untitled` or `namelessly beautiful`. Only, just then the painting was getting (entitled to) a name. I loved it and was thinking of the Dutch poetess Neeltje Maria Min and her `for the one who loves me I will be named`. Suddenly the work would be named `The Adoration of the Shepherds`, and one of those stars stood still so on reflection I called the painting `Sainte Chapelle`. Causing some uncertainties of nomenclature. The shepherds emancipated, becoming kings, magicians, astrologers, and, for a change, the painting was now named `Twelfth Night` or `The Journey of the Magi` – and what was that festival called again in Greek? Yes, Epiphany.

`Epiphany`, meaning `appearance` (to the heathens, the foreigners and us, to be precise). What did appear in Nazareth, what did reveal itself there? Something, anyhow, with claims to the name of `firmament`, a nocturnal phenomenon radiating appreciably more light in Galilea and Bosnia than it does north and west of these, whether that be Genova, Gelsenkirschen, Goteborg or Gennep.

Yes, behold the verbal byways one must travel in reaching sacred places and in defining one’s quiet adoration of a work of art which has mastered its foreign, Neanderthalian languages and its Dutch – High Netherlandish – so perfectly. As well as that language which is so eloquently mute that one is tempted to become verbose. As at this moment.

Mirso is star-struck. The second painting he presented to me was almost as `astral` as `Epiphany`, even though it `showed` and `indicated` more about our world. For instance? Well, simply a street in a town, called Sarajevo or Dubrovnik, those ideal places where Mirso was born and bred. High above nocturnal Sarajevo the stars are spotted and identified: first Mars, than Venus, first war than sex, or rather love and what passes itself off for it in this existence down below. Between that town and those stars there is no (Southern) Cross but there is a half moon.

Is the title of this painting indeed `Dubrovnik`? Or would `Last time I saw Sarajevo` be even more suitable?

Up to this point I had moved in the realm of magic, poetic, not to mention orphic, art. An art, it might be claimed with slight exaggeration, which is the especial reserve of artists deriving from regions east of us. That’s where they know best how to paint such sacred nocturnes, how to perform the astral liturgy. Mirso Bajramovic too is one who paints `Hymns to Night`. He too follows Jean Cocteau’s poetical direction of `carrying night through day`, extending the possible world of the dream into the profane world of up-to-datedness.

But he is not just a painter of nocturnes and `Night thoughts`. He is also a commonsensical man with a Western inquisitiveness about the system, the anatomy of romantic imagery. I say: part of his art is about art and even that Art creates art. This did not make him a post-modernist. To him the modern tradition is not `old news`, a decrepit archive, `Yesterday’s Papers`, from which one may legally quote from memory. No, he remained IN the tradition. Which is still as fully operative in former Yugoslavia as it is in the whole of Europe.

So Mirso Bajramovic is not simply an artist who carries night through day, he also wants the sun to shine in the darkness, make the light of reason clarify the dream. Or rather: he comes up to the arch-aphorist Karl Kraus’ expectations about people who dare call themselves artists: `An artist is someone who manages to change a solution into a mystery.` What does he do with that mystery, this happy artist? No, he does not solve it. He starts to search for her whom G.B. Shaw named `the sphinx without mysteries` – the muse, maybe. What she does and wants Bajramovic to do, what she still has in store for him, is and should be a mystery for now. What is certain, notwithstanding, is this: first Bajramovic silenced me, then he made me speak interminably. May I be forgiven for both.

Mr. Maarten Beks